- Signpost

- Posts

- 🇮🇩 Indonesia: Proclamation of Independence (1945)

🇮🇩 Indonesia: Proclamation of Independence (1945)

How two sentences united 17,000 islands

Analysing how language builds trust and enables power.

Hi Signposter. When it comes to geopolitical influence and power, there’s no substitute for size. For example, in South Asia (where I’m from), that moniker goes to India. In the Gulf (where I grew up), the biggest economy/political power/geographic nation is Saudi Arabia. In Southeast Asia (where I live) that title is easily won by Indonesia.

Indonesia is so large it shares maritime borders with India and Australia. It is the world’s largest archipelagic state (with over 17,000 islands, many uninhabited), the world’s fourth most populous country (after India, China, and the United States), and the largest economy in Southeast Asia. Jakarta, the largest city in the country, is situated in the world’s most populous island, Java.

All this is to emphasise simply how large, diverse, and disparate a nation Indonesia is. It’s a big place.

And yet the document that brought the nation together is uniquely small. That document is the focus of this week’s issue of Signpost.

TEXTS THAT SHAPED THE WORLD #3

📜 Proclamation of Indonesian Independence - 1945

Here is the entire text of the declaration, translated into English and taken verbatim from American historian and political scientist George McTurnan Kahin’s text named Sukarno’s Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, with specific words and phrases highlighted for semiotic analysis below:

PROCLAMATION

WE THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA HEREBY DECLARE THE INDEPENDENCE OF INDONESIA.

MATTERS WHICH CONCERN THE TRANSFER OF POWER AND OTHER THINGS WILL BE EXECUTED BY CAREFUL MEANS AND IN THE SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME.

DJAKARTA, 17 AUGUST 1945

IN THE NAME OF THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA

SUKARNO—HATTA

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

1️⃣ What was happening?

During the events of the Second World War, Japan had occupied much of Southeast Asia, taking over the region from European colonial powers. This included Indonesia, or the Dutch East Indies as it was then called, whom the Japanese had taken over from the Dutch in 1942. While several Indonesian independence movements had existed for decades under Dutch colonial rule, it was only towards the end of the Second World War when a unique set of circumstances aligned to allow for the country to take a bold step towards political independence.

Towards the end of 1945, as Japan’s colonial powers waned and their territorial expansion halted, the end of the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asian nations was self evident. Fully aware that they would surrender these territories back to their European belligerents, Japan began supporting the independence movement for Indonesia, hoping to create more issues for the reoccupying Dutch forces at the end of World War II.

On 15th August 1945, Japan surrendered, but Japanese troops were told to stay in Indonesia until the arrival of Allied troops. Already in direct talks with Indonesian leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, the Japanese maintained that they would not reject an Indonesian declaration of independence as long as it was not associated with the Japanese. Younger political leaders, including Wikana and Chairul Saleh, persuaded Sukarno to unilaterally declare independence before the arrival of the Dutch, knowing that he was the only person in the country who could legitimately make such a move. After heightened tensions between the younger and older Indonesian parties, leading up to the Rengasdengklok Incident, Sukarno agreed to declare independence for Indonesia within a larger speech made by him on the 17th of August.

2️⃣ Who wrote this and to whom?

The initial draft of the proclamation authored by the younger Indonesian political leaders was rejected by Sukarno for fears it would spark violence and backlash from the Japanese retreating forces and the incoming Dutch ones. The final text was drafted by Sukarno, to be included in his own speech the next day.

ANALYSING THE TEXT

Words / Phrases | What it Says | What it Means |

|---|---|---|

PROCLAMATION | An announcement | An announcement that is not tied to any specific ideology |

WE THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA | Representative of the Indonesian peoples | Not the message of any specific person or ideology, but the collective |

DECLARE THE INDEPENDENCE OF INDONESIA | a declaration of national independence | a declaration of national independence from no one in specific |

TRANSFER OF POWER AND OTHER THINGS | an important transfer of administration | not specifically referencing a transfer of sovereignty |

EXECUTED BY CAREFUL MEANS | with order, control, and process | without the radical energies of younger political leaders |

SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME | as soon as possible | before the arrival of the recolonising Dutch powers |

1945 | the year of our lord 1945 | the original text written by Sukarno mentioned the year as ‘05’ which referenced the Japanese imperial year 2605 |

SUKARNO—HATTA | the signatories of the text | the political leadership of the independent nation of Indonesia |

IMPLICATIONS

🫱🏼🫲🏽 TRUST: Then and Now

Much of the text was designed to not offend any major political stakeholder, or rather to equally offend everyone. By not officially mentioning either Japan or the Netherlands in the declaration of independence, Sukarno and Hatta minimised any political pushback from either colonial power. While the younger leaders wanted stronger language, they were able to interpret the phrase ‘shortest possible time’ as an indication that the independence of Indonesia would be organised prior to the re-arrival of the Dutch.

Meanwhile, the older leaders did not want any involvement from the younger leaders in the declaration, and were able to interpret the phrase ‘executed by careful means’ as an indication that there would be no rash youthful exuberance in the process. The phrase ‘transfer of power’ was broad enough to be interpreted by all parties to mean exactly what they wanted it to mean — a transfer of administration, rule, sovereignty, or control.

This helped to build some trust across the spectrum of powers with stake in Indonesia’s independence, from the colonial class, to the ruling class, to the working class.

👑 POWER: Then and Now

Many Indonesians celebrated the declaration, but many more were not convinced that such a declaration was real and not a ploy by retreating Japanese forces. Sukarno and Hatta became Indonesia’s first president and vice-president respectively shortly after, ratifying the constitution.

Meanwhile, the Dutch attempted to reestablish control over the Dutch East Indies, and engaged in a violent conflict with Indonesia until 1949, before officially recognising the sovereignty of Indonesia, four years after the declaration.

The largest nation in the region was finally officially independent.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO?

It’s August 1945. The Japanese colonial powers are retreating from Indonesia, and you, an important member of the Indonesian independence movement, are charged with drafting a proclamation of independence from both the retreating Japanese and the arriving Dutch colonial powers.

Tell me your reasoning. In next week’s issue, I’ll highlight the most thought-provoking responses.

LAST WEEK’S RESPONSES

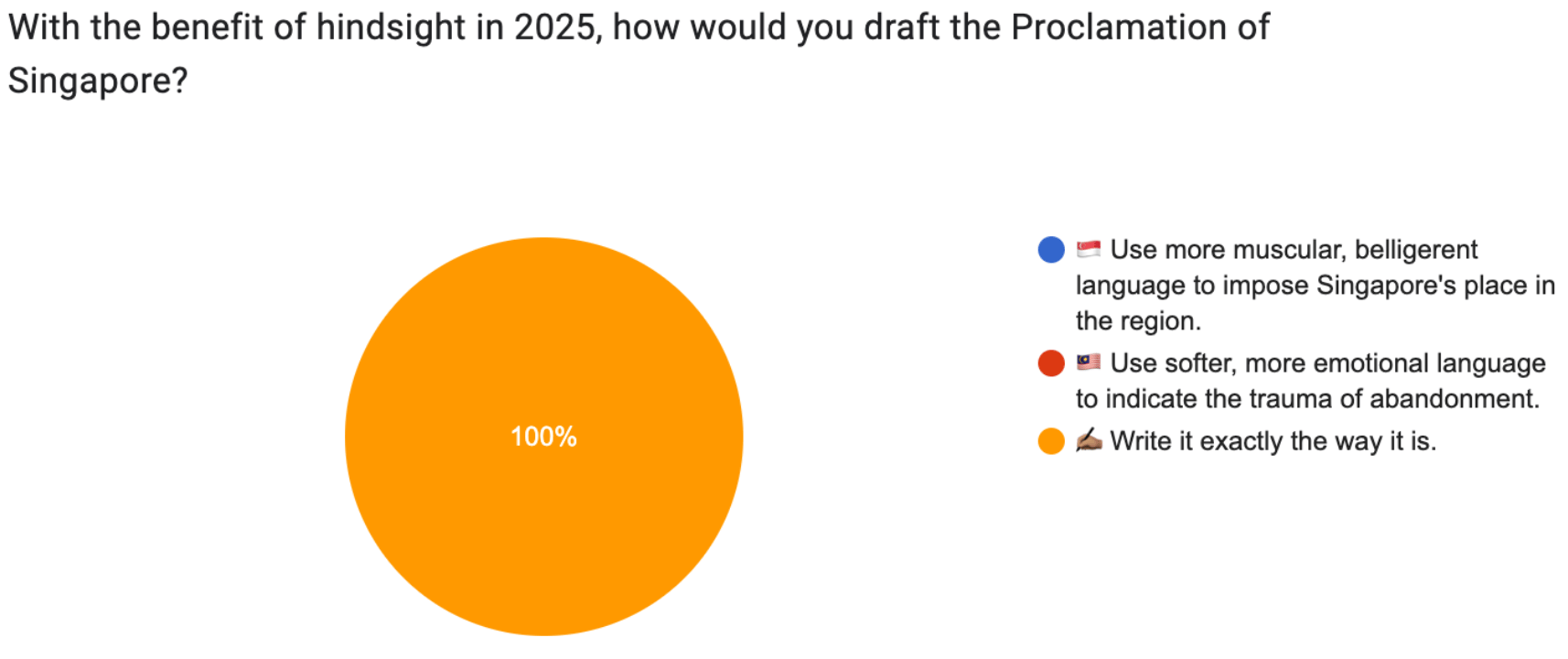

Pretty much expected this response.

NEXT WEEK ON SIGNPOST

Next week, we look at Tryst with Destiny, the famous speech that announced the arrival of the world’s most populous democracy, India.

Was this forwarded to you? Signpost is a free weekly newsletter analysing historical declarations and modern opinion pieces, what they mean, and why they matter. It’s free to subscribe. Think somebody else would enjoy this? Send them here.